Minera Lead Mines & Country Park

Visit Minera Lead Mines and Country Park for a fascinating glimpse into the industrial past of the beautiful Clywedog Valley. Situated at the head of the valley, Minera is a great starting point for the Clywedog Trail or for accessing the beautiful countryside of Minera Mountain. Enjoy a picnic or take a walk along the old railway line and explore Minera Lead Mines Country Park.

Visitors to the museum can explore the remains of the lead processing areas from the 18th and 19th centuries and the restored beam engine house, winding engine and boiler houses. From the top of the Beam Engine House there are fine views of the site and surrounding countryside.

Covering 53 acres of grassland, wooded areas and archaeological sites Minera boasts a great variety of wildlife and endless opportunities to explore in peace and tranquillity.

The dramatic Minera Mountain adjoins the park to add even further interest for dedicated walkers.

A picnic site with scenic views over the valley makes for a great afternoon at Minera Lead Mines and Country Park.

Riders & cyclists can use the path along the old railway line. There is ample parking in the car park.

Directions

Leave A483 taking A525 signposted Ruthin. At Coedpoeth, opposite the Five Crosses Pub take B5426 (Minera Hall Road) signposted Minera and follow this road for just over one mile until you reach the site entrance and car park on the right. Look out for brown signs marked Pyllau Plwm Lead Mines.

Sat Nav: LL11 3DU

The Story of Minera Lead Mines

Below Minera lies a valuable metal that people have used for over 8,000 years – lead. At Meadow Shaft (the site of the Minera Lead Mines visitor centre) the lead is deep underground. However the first mines were up on Eisteddfod and Esclusham Mountains, above Minera, where the lead is at or near the surface.

© Courtesy of Denbighshire Record Office

The first written record of the lead miners of Minera dates from 1296 when Edward I hired them to work in his new mines in Devon. The miners were ordered to present themselves for service. They did not all go as the Minera lead mines were worked until the Black Death (1349).

© Courtesy of Georgius Agricola & Carl Parry

During the 15th century there was little mining activity as Owain Glyndwr’s uprising and the Wars of the Roses caused a downturn in the economy.

Under the Tudors (16th century) local landowners and merchants regularly tried to get the lead mines working again. They were rarely successful.

In 1527 Sir John Chilston and Launcelot Lowther, two local officials, paid 20 shillings a year to have the local lead mining rights. These included:

“all mines of lead, open and to be opened, left and not occupied or used out of memory, with full power, liberty and authority to dig, sink, try, open, search and find out all manner of lead, lead ore, or packs of lead.”

Sir John Chilston and Launcelot Lowther

They also had the rights to mine coal and quarry stone. Yet still they could not make it pay. Only the owners of the mineral rights, landowners such as the Grosvenors, made any money.

Medieval Miners

The lead miners of Minera in the Middle Ages were a distinct community. Both English and Welsh men came to work the mines at Minera. The medieval miner was usually a farmer. He did his mining in the early summer in that quiet time before harvest. Mining stopped during harvest and over winter.

© Georgius Agricola & Carl Parry

The miners had rules on how to mine. Whenever a new vein of lead was found, the miners elected a bermaster. The bermaster ensured the new find was divided up fairly. The miners either dug a series of shafts or followed the vein by digging a huge groove in the ground.

© Georgius Agricola & Carl Parry

The miners did all the jobs: mining the ore, separating the valuable metals from the waste, and smelting the lead. The miners had to pay the landowners a fee, known as ‘loot’ or ‘lot’, on all lead sold. Breaking the rules could result in harsh punishment:

.If he be attainted of carrying away ore a third time, his right hand shall be pierced by a knife through his palm and pinned to a windlass (1) up to the handle of said knife. There he shall remain until he be dead or shall have freed his hand from the aforesaid knife. And he shall forswear his franchise of the mine and if he have a meer (2) in the mine it shall be forfeit to the lord.

Mining Laws, 1391

It was a tough job and if they did not make any money the miners went back to their farms.

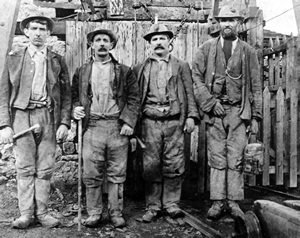

Modern Miners

Lead miners in the 18th & 19th centuries were equally independent. The modern lead miner was more a contractor than an employee. The miners worked on a bargain system. Miners had to be skilled negotiators. They would agree with the agent to work a vein for an agreed price per ton. The fee would vary depending on the difficulty of the job. Miners also bargained over the pay for sinking shafts and driving levels.

© Denbighshire Record Office

Traditionally, the miners shouldered the risk as they hoped to strike lucky by hitting a wide vein of lead. As the lead reserves ran out, the regular pay of work in the coal mines proved too tempting. By the late 19th century, the Minera lead mining companies found it difficult to keep their skilled workers.

“The nature of their employment is obviously unwholesome. Their appearance denotes an imperfect state of health, it being commonly pale, wan and weakly”

Revd. Richard Warner

There was not just the risk of no money. Lead mining could seriously damage your health. Few miners lived to be fifty. The dust from the drilling caused silicosis, a disease of the lungs. The new compressed air drills, introduced from the 1870s, made matters worse.

Accidents were common. Between 1873 when records began and the mines’ closure in 1914, 27 people were killed working at Minera lead mines.

© Denbighshire Record Office

Mining Heyday

The boom times at Minera lead mines started in the 18th century.

Prospectors had learned how to find the underground reserves of lead. However, deep mining had its problems. The lead veins (1) are in limestone. Limestone means underground rivers so flooding in the mines was always a problem. Pumping this water out was costly and a major obstacle to any successful deep mining for lead.

The man with the solution in the late 18th century was John Wilkinson, entrepreneur and the brains behind Bersham Ironworks. Wilkinson’s steam engines were the best yet at keeping the mines free of water. Lead mining was once again profitable. Unfortunately, Wilkinson did not tell Boulton & Watt about his pirated copies of their steam engines. They found out and Wilkinson had to pay up.

Those pumping engines were vital. When problems with the pumps and disputes over paying for the engines led to the pumping stopping, the mines once again closed.

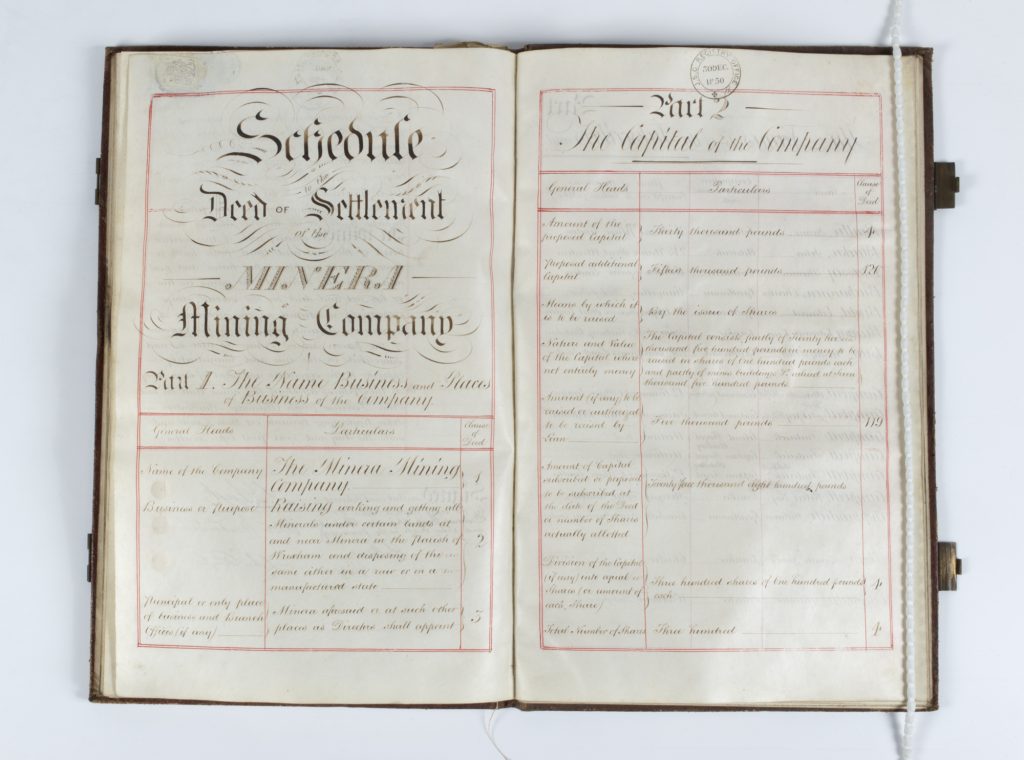

In 1845 John Taylor & Sons, mining agents from Flintshire, formed the Minera Mining Company. They had the experience. They knew Minera’s lead mines had potential. They consolidated the mining leases, put in a new drainage level from Nant Mill to get water out of the mines and invested in new engines and a new railway line. In 1852 lead ore was, once again, being mined at Minera.

The miners discovered new reserves of lead deeper underground. It was boom time. The Taylors had started off with £30,000 to invest in their mining venture; the profits for 1864 alone were over £60,000.

© Denbighshire Record Office

The good times continued into the 1870s, but there were problems ahead. The price of lead started to fall, while the price of coal to keep the pumping engines running rose. Reserves of lead were starting to run low. Zinc, the other metal mined at Minera, also fell in price. By the late 1890s, mining at Minera no longer made much economic sense.

In 1909 the mining company decided the pumping engines were too expensive to run. The mines started to flood. In 1914 lead mining stopped. The machinery was sold and the last few miners helped the owners salvage the remains of the business. It was the end of an era for Minera.

Ups and Downs

The Good Times & the Bad Times at Minera Lead Mines

In 1885 the price of lead was at rock bottom. Sir Theodore Martin, chairman of the Minera Mining Company, spoke to a packed election meeting:

“This mine has been a mine of great wealth, not only to those who have embarked their capital in it, but also to the working man who found employment there. I have seen the mine’s inception, I have witnessed its days of great prosperity and I have watched its days of partial decline, but I have never lost my confidence in the good old mine.”

Sir Theodore Martin

Sir Theodore was not the first optimist to put money into Minera. The mines had always had their ups and downs.

The 1860s were boom times, yet fortunes could change very quickly. A fall in the price of lead or zinc could be disastrous.

In 1872 the Minera Union Mining Company, which had mines to the north-east of the Meadow Shaft complex, had to ask its shareholders to bail the firm out. Their reports on future prospects in the mine betray an air of desperation. The South Minera Mining Company had even less success; ten years of investment and only a few tons of ore to show for it.

In 1887 the Minera Mining Co. faced tough choices. Zinc had been a good source of profits when sales of lead were down.

“It has become indispensably necessary to consider what steps should be taken to restore the prosperity of the mine. The Smelting Companies are, by arrangement amongst themselves, able to dictate the price of blende (zinc). This they have done with such success as to have reduced it to a figure below, in the case of our ores, the actual cost of production.”

Minera Mining Company, Annual Report, 1887

Consultants were brought in from Germany. They recommended opening a smelter at Minera, just up the hill from the Meadow Shaft. In effect cut out the middleman. Profits of 10% a year were talked of. The smelter opened in 1888, but never made any money and closed within five years.

Money was made at Minera, but much was lost. That was the story of Minera Lead Mines.

The Life of a Miner

Simon Hughes

Simon Hughes was born in 1872. He lived with Ellen, his wife, and their nine surviving children in New Brighton.

He was a skilled worker and a master of several trades. His job was to repair and keep in good order all timber in the mine. He had to ensure all the shoring and propping of loose ground, make and fix ladders and lay rails for the tramways. On top of this he helped to maintain the pumps, pipes and associated equipment. When the company needed an extra man, Simon worked on the ore crusher.

Simon Hughes usually worked a six day week. It was a six hour working day excluding breaks. It was hard physical work and there were no paid holidays. His pay varied depending on the work he did. By the time he finished at the mine in 1915 he was on four shillings and six pence (about 22p) a day, though sometimes his wage was as low as a shilling and tuppence (about 6p) a day.

He was surely a valued employee as the United Minera Mining Company employed him to the very end. Luckily he avoided the job his colleague, William Williams, had to do for several months – cleaning bricks from the demolished mine buildings for re-use; fourteen thousand of them in November 1914 alone for just £3 3s. More importantly Simon survived his career in the lead mines – not everybody did.

© Denbighshire Record Office

A Dangerous Place

In the 1800s, Health & Safety meant looking after yourself and each other. Only in 1873 did the government decide to start checking if lead mines were safe places to work. They weren’t.

Terrible Mining Accident at Minera

Shocking Death of Four Men

“A terrible accident occurred at the United Minera mine on Wednesday night in which four men were instantly killed in the most shocking manner. About 10.30 on the night named, four men, forming part of the night shift, were being lowered by a carrier down what is known as the Meadow Shaft, when, through some defect, the main eyebolt from which the carrier was suspended broke when a descent of about 180 yards from the surface had been made. The carrier containing the four men was precipitated to the bottom of the shaft, a depth of something like 400 yards and there smashed. The men of course were instantly killed. Their names were, Enoch Jones, married; John Foulkes, single; David Davies, single and Donald Douglas, single.”

Wrexham Advertiser,

9 February 1901

An inquest was held at a local pub. The mining company said that the bolt was designed to carry five tons. The cage with the men weighed less than a ton. The coroner questioned why there were no chains attached to the cage as a precautionary measure. The Inspector of Mines had passed the cage as safe, so the company had not thought there was any need for bridle chains.

© Denbighshire Record Office

The coroner summed up: ‘Of course, there is absolutely no blame on the company for not having the chains put there. It is quite impossible to say how this accident happened, but it showed the desirability of making the carrier doubly safe.’

The result: the jury returned a verdict of accidental death. Mr Wynne, the Company Secretary, ensured chains were added to the cage. Enoch Jones and John Foulkes were both buried at the Wern Chapel burial ground, just along the road from the Minera Lead Mines site. Donald Douglas was buried in Chester and David Davies in Minera churchyard. Four lives had been cut short and one widow and five children bereaved.

Heavy Metals

© Denbighshire Record Office

Lead

People have used lead for over 8,000 years. It is malleable so it was easy to work it into useful objects. It is resistant to corrosion, so lead objects had a long life.

The Romans used lead for their water pipes. Our word for plumber comes from ‘plumbum’ the Latin word for lead. In medieval times lead was used as loom weights and for the roofs of churches, monasteries and castles.

Lead was used in mirrors, pewter and in glass. By the time of Elizabeth I lead was used in make-up, while the new muskets fired lead shot.

In recent times lead has appeared everywhere: in paints, in batteries, as solder and in tin cans. Unfortunately, lead has proved to be both poisonous to people and animals. Consequently, nowadays its use is limited.

Zinc

The Greeks and Romans used calamine, a natural form of zinc, to make brass. The calamine when added to copper made a very yellow alloy that was highly sought after. Yet no-one discovered zinc itself until 1520.

In the 19th century, industrialists mastered the practice of galvanising iron using zinc. The zinc stopped the iron from corroding. One product, corrugated iron, caught on quickly. Countless industrial buildings had roofs made from corrugated iron. Sometimes even whole buildings were made from it.

© Denbighshire Record Office

The Meadow Shaft Engine House

Owen Jones first bought land at Minera in the 17th century. He died in 1659 and bequeathed his property, then just poor farmland, to the city companies of Chester to look after the poor. The companies’ officials did well out of the bequest. The poor, however, did not.

The Minera Lead Mines visitor centre, the Meadow Shaft Engine House and the dressing floors are all on the City Lands. The engine house is also known as the City Engine House. The local pub is the City Arms.

The mine became a success story in the 18th century. Between 1761 and 1781, the city companies as owners of the mineral rights received nearly £13,000 in royalties.

The mine flourished again after 1849. The Minera Mining Company invested in a new pumping engine in 1857. A year later they installed a new winding engine to raise the lead ore and to work the mechanical ore crusher. Soon after the company built new ore bins, dressing floors for sorting the lead from the waste and the ore house for drying, weighing and sampling the lead ready for sale. All this equipment enabled miners to mine ore from the deepest veins in Minera, up to 400 metres below the surface.

In 1884 a new dressing floor was opened at Roy’s Shaft with all the latest machinery. The Meadow Shaft site became a dumping ground. Gradually the dressing floors were buried. Only the actual Meadow Shaft remained in use and it closed in 1914.

© Denbighshire Record Office

© Denbighshire Record Office

Minera Uncovered

Mining ceased in 1914. Up to the 1950s the enormous spoil heaps were worked for gravel, leaving a toxic lunar landscape.

The lead, zinc and cadmium in the spoil heaps, being heavy metals, posed a threat to water supplies. The dust was also a problem. Wrexham Maelor Borough Council and the Welsh Development Agency devised a scheme to make Minera Lead Mines safe.

Work started in 1988. Hidden beneath the spoil heaps was the evidence of the old lead-mining industry. As reclamation continued, so Minera’s past was uncovered. The spoil heaps had protected the archaeology. Once uncovered, the remains could rapidly decay. Difficult choices had to be made.

At Taylor’s shaft the excavations revealed how lead-mining technology changed in the 19th century. While at Meadow Shaft the whole journey of lead from the pit head to saleable ore can be seen by a tour round the site. The lead miners’ personal belongings were also found at the Meadow Shaft site. These finds made the Meadow Shaft site ideal for historical reconstruction. In the early 1990s, the buildings and the dressing floors were rebuilt or consolidated. Replica machinery was installed based on the archaeology of the site.

Work is still ongoing. The weather, people and landslides all take their toll on the site. Wrexham County Borough Council look after Minera Lead Mines and ensure it is open for visitors to see what is left of this fascinating part of our industrial heritage.