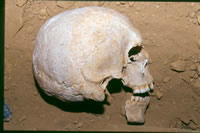

In August 1958 local workmen were digging a pipe trench near No.79 Cheshire View, Brymbo, near Wrexham, when they found more than they expected: a large capstone about 30 cm (1 ft) below the surface. They had found Brymbo Man

Brymbo Man – What do we know?

Age: about 35

By checking the wear on his teeth and the fusion of the bones in his skull.

Date of Birth: c.1935 BC

By identifying the beaker as a “Short Necked” type made about 1900BC

Height: 5’8″/173cm

By measuring his tibia (a lower leg bone). Its length is in proportion to his height.

Build: Stocky

The shape of his skull and the muscle attachments to his skull and leg bones show that he was a powerfully built man.

Distinguishing Features: Wound above hairline on forehead

Distinguishing Features: Wound above hairline on forehead

By closely examining the damage to the skull, we can tell that he survived the wound because we can see it healed. The teardrop shaped pit points to an arrow being the probable cause.

Post Mortem Events

Post Mortem Events

By examining the bones closely, the bone specialist noticed cut marks made with a sharp instrument. Perhaps their burial practices involved de-fleshing the bones.

Religious Affiliation: Belief in the afterlife

The Beaker may have contained a drink for his journey in the afterlife. The flint knife was perhaps there for Brymbo Man to prepare a snack on the way.

Age:35

Date of Birth: about 1935 BC

Address: nr Bryn-y-ffynnon, now known as Cheshire View

Nationality:not applicable

Height: 5’8″ / 173cm

Hair: BrownBuild:Strong/Stocky Athletic/Muscley/

Distinguishing Features:Arrow wound above hairline

Qualifications: Basic Farming (crops & animal husbandry); Flint knapper; Survival skills; Herbal medicine

Occupation:Farmer, Hunter and Fighter

Hobbies: Working with skins, bone and horn; storytelling

Beliefs:In the afterlife and in the new Bronze Age ideas from the south-east

Ambitions: Learn how to work bronze

Favourite possessions: Beaker and best flint knife

A glimpse into the world of Brymbo Man

- He had his home in a farming community and lived off the land.

- His community was in contact with the outside world: Bronze Age boats have been discovered in the Humber estuary, grave goods include products not available locally such as amber from Scandinavia and faience from Egypt. Trade also brought new ideas such as metal working.

- Perhaps he was keener on new ideas than people further west. In Gwynedd the tradition of communal burials continued into the Bronze Age. In North-East Wales different burial practises existed alongside each other. The new ideas included burying people on their own under stone and earthen mounds, known as barrows.

- It is hard to say how many people lived in Early Bronze Age Wales. The estimates range between 10-20,000.

- The weather was warm and dry enough for farmers to use the uplands for pasture and growing crops.

- Lowland areas were thickly wooded, upland areas were not.

Brymbo Man : The Evidence

To understand Bronze Age Britain we have to rely on the study of monuments and finds that have survived into the present day.

In the case of Brymbo Man, what do we have to go on?

The Skeleton

The Skeleton

Pathologists can by examining a human skeleton tell us much about the person when alive: the person’s age, sex and height, their diet, where they grew up and the cause of death.

The Beaker

The Beaker

The type of pottery, its shape, fabric and decoration are all clues. Archaeologists know beakers changed over time. They use these clues to work out the approximate date of manufacture.

The Flint Knife

The Flint Knife

As with pottery, it is possible to roughly date a flint knife by looking at its shape and its cutting edges. You look for similar flints the age of which are already known.

The Stone Cist

The Stone Cist

They were a common feature in the Early Bronze Age, especially in Beaker Burials.

Creating such a grave required a lot of work. What kind of person would merit such a grave? Was he special or are there many similar tombs out there undiscovered?

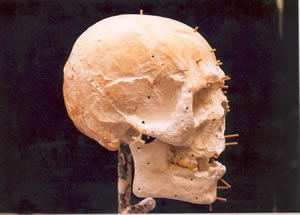

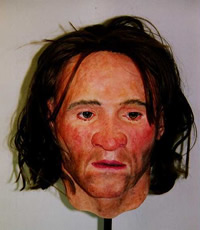

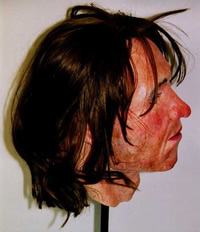

The Reconstruction

You can tell a lot about a person from their face. Now with expert help, you can recreate a human face from its skull.

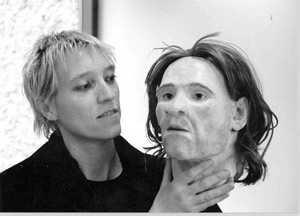

One of the top experts in facial re-construction is Dr Caroline Wilkinson. She worked at the Unit of Art in Medicine at Manchester University, where Brymbo Man was sent for his “makeover.”

First question: Was there enough left of Brymbo Man’s skull for a reconstruction? Just! His skull is not complete: only the chin of his lower jaw remains and part of the left side of his skull has gone. There was enough for Caroline to work on.

Caroline made a cast of the skull. Brymbo Man’s skull is too old and fragile to be used for the reconstruction. The skull is real history so it had to be protected from irreversible damage. To make the cast, Caroline had to make a mould. She sealed the holes in Brymbo Man’s skull and then covered the skull in aluminium foil to protect it during the making of the mould. The moulding material, exactly the same as that used by dentists for impressions, is like porridge and is spread all over the skull. Once it set, a perfect cast of Brymbo Man’s skull could be made.

The next step for Caroline was to tap in the little pegs to indicate the flesh thickness at twenty-one different points on the skull. The measurements are decided by sex, age and ethnic group. The shape of your face is also determined by your weight. We did not know whether Brymbo Man was skinny or fat so his pegs were based on the ‘average weight’ measurements.

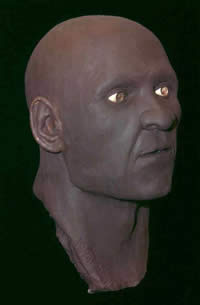

Caroline then added the main muscles in clay. She noted the position and strength of the muscle attachments or insertions on the skull. These indicate the strength of the facial muscles and consequently the shape of Brymbo Man’s face.

Nearly every feature of the face is determined anatomically for instance:

- The width of the mouth by the outer borders of the canine teeth or the inner borders of the iris in the eyes.

- The width of the nasal aperture in the skull is about 60% of the width of the nose.

- If you draw a line from the lower third of the nose bone and another from the nasal spine at the bottom of the nasal aperture, where the two lines cross is the tip of the nose.

- The angle at which the eyes slant can be determined from the skull based on the angle between the hollow for the tear glands and a little bump on the inside of the orbit (the eye socket).

It is not guess work or imagination. It is this methodological approach that ensures that the re-construction of Brymbo Man’s face is as true to life as possible.

The skin is added in clay strips guided by the little wooden pegs. All the time Caroline also takes account of the muscle structure she created initially. Some things are difficult to decide exactly: lips and ears are particularly tricky. The skill is ensuring that the choice made fits in with the rest of the face. No-one who has had cosmetic plastic surgery could be replicated from their skull or at least not how they looked post operation. Caroline did the final modelling relying on her experience over the years in facial reconstruction work.

Caroline & Brymbo Man

Brymbo Man’s next journey was to London to visit the make-up artist. She added hair and eyebrows. Decisions on hair and eye colour are difficult. Many of the choices are based on suppositions about the past that reveal more about archaeologists and pre-historians who make them than what was reality. By giving Brymbo Man brown hair and hazel eyes the question of his exact origin is left open for further discussion. He spent a lot of time out of doors so he needed a weather beaten look. We don’t know whether he was clean shaven or not, but they did have razors in the Early Bronze Age.

Now he has returned to the Museum, you can see the finished re-construction for yourself. That is how he looked. Not so different from us after all.

As poles to tents and walls to houses, so are bones to all living creatures

Galen, De anatomicus administrationibus, 2nd Century AD

It is the common wonder of all, how among so many millions of faces, there should be none alike.

Sir Thomas Browne, Religio Medicii, 1643

Brymbo Man: Burials

Brymbo Man has been of such interest to archaeologists because he is rare: a Beaker burial in Wales.

So little remains of the lives of people in prehistoric times that burial sites are more important in telling us about them than our graveyards will ever be in telling the future about us.

In their world view, death was ever present in their lives. Consequently the changing burial practices of people in the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages helps to reveal their belief and social systems.

Neolithic Burials

- People buried in groups; children and adults together.

- Community more important than the individual.

- Perhaps also sited where the community felt threatened by nature or other people as a property claim

- Long cairn found at Tan-y-coed in the Dee Valley.

- Round cairn found at Gop Cairn, nr Prestatyn. The second largest prehistoric man-made mound in Britain. To build something so big meant that community was saying something important.

Beaker Burials

- Time of change during the late Stone Age and early Bronze Age led to changes in societies, beliefs and customs.

- Burials became more individualistic. People buried on their own.

- The dead took personal belongings with them – jewellery, arrow heads, weapons such as axe-heads, flint knives and metal work. These objects reflected status and aspirations while alive. Perhaps they had symbolic rôles in the afterlife.

- Beaker Burials are the first burials to contain personal belongings with the body.

- The Beakers were important enough to be put in the graves.

- These sites are smaller than the communal sites of the Stone Age and fewer have been discovered/have survived.

Understanding Prehistory

Prehistory is what historians call the period before people learned to write. In the case of Britain it means everything before the Romans. Most of the past, in fact.

In prehistory, it is very difficult to be exact about dates. The periods of time you deal with are so big, academics give them names. No one then thought in this way.

- Palaeolithic = Old Stone Age 250,000 to 8000BC

- Mesolithic = Middle Stone Age 8000 to 4300BC

- Neolithic = New Stone Age 4300 to 2300BC

- Bronze Age 2300BC to 600BC

- Iron Age 600BC until the Romans

Remember, the boundaries between each period are very flexible especially during academic discussion. They also vary depending on what part of the world you choose.

Things did not suddenly shift gear in 8000BC, 4300BC, 2300BC or 600BC. Much as things didn’t change on January 1st 2000.

What do we know about the Bronze Age?

- It comes between the Stone Age and the Iron Age.

- It is the first time people use metals for tools and weapons.

- It lasts from roughly 2300 to 600BC. This is about the same span of time as from the end of the Roman Empire to today.

- It is a time of change with the appearance of new beliefs and customs.

- It is the first time personal belongings are buried with the dead; perhaps for use in the afterlife.

Distinguishing Features: Wound above hairline on forehead

Distinguishing Features: Wound above hairline on forehead Post Mortem Events

Post Mortem Events The Skeleton

The Skeleton The Beaker

The Beaker The Flint Knife

The Flint Knife The Stone Cist

The Stone Cist